Seleukid Study Days VIII:

The Afterlife of the Seleukids

Receptions and Reinterpretations from Antiquity to the Present

Utrecht, 12–15 November 2025

Co-Hosted by the Waterloo Institute for Hellenistic Studies

(updated 12 November 2025)

University Library Utrecht Science Park (USP)

Address: Heidelberglaan 3, 3584 CS Utrecht, The Netherlands

Conference Room: Bucheliuszaal (Room 6.18)

The Utrecht Science Park is easily reachable from Utrecht city centre or central station by bus or tram (15-20 minutes).

Stratonice and Antiochus, Jean Grandjean (1775), Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, RP-T-1921-66

-

In recent decades, new studies on the Seleukids have reevaluated the empire’s significance for the longue durée of Ancient History (see e.g., Engels 2011; Strootman 2012; Strootman & Versluys 2017; Canepa 2018; Erickson 2018). No longer seen as a European-style state identified with Syria, recent publications have emphasized that the Seleukid ‘kingdom’ was a universalistic empire, pointing out the pivotal importance of Mesopotamia and Iran for Seleukid rule (Van der Spek 1987; Wiesehöfer 1994; Sherwin-White & Kuhrt 1993; Kosmin 2014; Engels 2017; Stevens 2019; Daryaee et al. 2024; Navas Moreno 2024). Located at the very heart of the Ancient World, the empire was neither simply ‘Eastern’ nor simply ‘Western’, and bridged the temporal and cultural divide between the Achaemenid empire and the Parthian and Roman empires (Engels 2011; Strootman 2014; Coşkun and Engels 2019). Merging Macedonian, Iranian, and Mesopotamian forms of kingship and imperialism (Anagnostou-Loutides and Pfeiffer 2022; Coşkun and Wenghofer 2023), Seleukid influence extended far beyond the empire’s collapse in the later second century BCE. The significance of the Seleukid court for the production of knowledge and literature is now also better understood (see e.g., Visscher 2020).

Already in Antiquity, civic communities and successor dynasties such as the Orontids of Kommagene and the Persian Sasanians actively engaged with the Seleukid legacy (Noreña 2016; Ogden 2017; Strootman 2021). The Seleukid role in the deuterocanonical tradition and the festival of Hanukkah engrained them in Jewish traditions, including still widely read folktales (Coşkun and Scolnic, in prep.). Seleukid coins have been collected and studied since the Renaissance. During the early modern period, the presence of Seleukid-related themes in European art, literature, and opera was ubiquitous, notably the story of Stratonice and Antiochus, which was retold many times on the theatrical stage and in paintings. In the twentieth century, Cavafy brought the Seleukid empire to life in his poems. More recently, the Seleukids made their mark on popular culture through modern media such as tabletop wargames, videogames, podcasts, YouTube, and comics.

Yet the impact and reception of Seleukid history and imperial culture have received very little attention in modern scholarship, and unlike the Achaemenids and Arsakids, the Seleukids still do not hold a place of their own in current reception studies. The aim of this conference is to change this and to open a new research field of Seleukid reception studies that does justice to the empire’s historical geopolitical significance.

For this two-day conference (with a reception the night before and a touristic field trip afterwards) we invite abstracts on the Seleukid afterlife in ancient, medieval, early modern, and modern times. What can we say about the ongoing prestige of the dynasty in Antiquity, as expressed, e.g., by the Philopappos Monument in Athens, the Alexander Romances, or the writings of Late Roman authors, such as Libanios and Malalas? How was its place in history perceived in premodern and modern historiography in Asia and Europe? How were the Seleukids and their ‘world’ represented in art, literature, and the theatre? We especially welcome presentations that engage with the Seleukids in the context of ‘western’ or ‘eastern’ identity. What is the role of Orientalist tropes in representations of the Seleukids, and how did the simultaneously existing European appropriation of the Seleukid empire as a ‘Western’ state impact non-Western views? Last but not least, we want to acknowledge the youngest phase of Seleukid reception: that of active production of art & literature, and thus invite creative contributions also from these fields.

Paper proposals, including title, abstract (250 w.) and short CV (up to 200 w.), can be sent by Jan. 31, 2025, to Altay Coşkun, Pim Möhring and Rolf Strootman at SSD8Utrecht25@gmail.com.

-

Anagnostou-Laoutides, E. and Pfeiffer, S. (eds.) 2022: Culture and Ideology under the Seleucids. Unframing a Dynasty, Berlin.

Canepa, M.P. 2018: The Iranian Expanse: Transforming Royal Identity through Architecture, Landscape, and the Built Environment, 550 BCE–642 CE, Berkeley.

Coşkun, A. and Engels, D. (eds.) 2019: Rome and the Seleukid East. Selected Papers from Seleukid Study Day V, Brussels, 21–23 Aug. 2015, Brussels.

Coşkun, A. and Scolnic, B.E. (eds.) in preparation: Judaean Responses to Seleukid Rule (Seleukid Perspectives 4), Stuttgart.

Coşkun, A. and Wenghofer, R. (eds.) 2023: Seleukid Ideology: Creation, Reception and Response (Seleukid Perspectives 1), Stuttgart.

Daryaee, T., Rollinger, R., Canepa, M. P. (eds.) 2024: Iran and the Transformation of Ancient Near Eastern History: The Seleukids (ca. 312–150 BCE). Proceedings of the Third Payravi Conference on Ancient Iranian History, UC Irvine, February 24–25, 2020, Wiesbaden.

Engels, D. 2011: ‘Middle Eastern “Feudalism” and Seleukid Dissolution’, in K. Erickson and G. Ramsey (eds.), Seleucid Dissolution: The Sinking of the Anchor, Wiesbaden, 19–36.

Engels, D.2017: Benefactors, Kings, Rulers: Studies on the Seleukid Empire between East and West, Leuven.

Erickson, K. (ed.) 2018: The Seleukid Empire, 281–222 BC: War within the Family, Swansea.

Kosmin, P.J. 2014: The Land of the Elephant Kings: Space, Territory, and Ideology in the Seleucid Empire, Cambridge, MA.

Navas Moreno, R. 2024: ‘The Frataraka of Persis’, Karanos 7, 71–97.

Noreña, C.F. 2016: ‘Ritual and Memory: Hellenistic Ruler Cults in the Roman Empire’, in K. Galinsky and K. Lapatin (eds.), Cultural Memories in the Roman Empire, Los Angeles, 86–100.

Ogden, D. 2017: The Legend of Seleucus: Kingship, Narrative and Mythmaking in the Ancient World, Cambridge.

Sherwin-White, S. and Kuhrt, A. 1993: From Samarkhand to Sardis: A New Approach to the Seleucid Empire, London.

Stevens, K. 2019: Between Greece and Babylonia. Hellenistic Intellectual History in Cross-Cultural Perspective, Cambridge.

Strootman, R. 2012: ‘The Seleukid Empire between Orientalism and Hellenocentrism: Writing the History of Iran in the Third and Second Centuries BCE’, Nāme-ye Irān-e Bāstān: The International Journal of Ancient Iranian Studies 11.1–2, 17–35.

Strootman, R. 2014: ‘Hellenistic Imperialism and the Idea of World Unity’, in C. Rapp and H. Drake (eds.), The City in the Classical and Post-Classical World: Changing Contexts of Power and Identity, Cambridge, 38–61.

Strootman, R. 2021: ‘Orontid Kingship in Its Hellenistic Context: The Seleucid Cconnections of Antiochos I of Commagene’, in M. Blömer, S. Riedel, M. J. Versluys, and E. Winter (eds.), Common Dwelling Place of all the Gods: Commagene in Its Local, Regional and Global Hellenistic Context, Stuttgart, 295–317.

Strootman, R., and Versluys, M.J. (eds.) 2017: Persianism in Antiquity, Stuttgart.

Van der Spek, R.J. 1987: ‘The Babylonian City’, in A. Kuhrt and S. Sherwin-White (eds.), Hellenism in the East: The Interaction of Greek and Non-Greek Civilizations from Syria to Central Asia after Alexander, Berkeley, 57–74.

Visscher, M. 2020: Beyond Alexandria: Literature and Empire in the Seleucid World, Oxford and New York.

Wiesehöfer, J. 1994: Die “Dunklen Jahrhunderte” der Persis: Untersuchungen zu Geschichte und Kultur von Fars in frühhellenistischer Zeit (330–140 v. Chr.), Munich.

-

Wednesday, 12 November

16:00-16:10

Arrival

16:10-16:20

Welcome & Introduction by Rolf Strootman, Altay Coşkun, Pim Möhring

Panel I: Reinventions of Antiochos’ Love Sickness

Panel chair: Rolf Strootman, Utrecht

16:20-16:55 (opening SSD8)

A Lovesick Prince in the Indolent East: Orientalism, Exotism and Colonialism in Western Images of the Empire "between East and West" from the Renaissance to the Present.

Rolf Strootman

16:55-17:30

The Anecdotal History of the Seleukids in the Second and Third Centuries CE

Eva Anagnostou-Laoutides, Sydney

17:30-18:05

Imagining the Seleukid Past in Late Roman Antioch: Intellectuals in the Face of Popular Power

Yanxiao He, Beijing

18:05-18:40

Good Father, Better Son: Reframed Kingship in Agustín Moreto’s Comedy “Antíoco y Seleuco”

Martin Parra, University of Michigan

19:15

Reception (place tba)

Thursday 13 November

Panel II: Remembering the Seleukids in the Hellenistic Cities of the Roman Empire

Panel chair: Miguel Versluys

09:00-09:35

Negotiating Empire: Seleukid Memory and History in the Narratives of Roman Cities of Asia Minor and the Levant

Rogier van der Heijden, Postdoctoral Researcher at the Humboldt University in Berlin

09:35-10:10

A Cosmopolitan City: Governing Roman Dura Europos through Myths of Seleukos and Alexander the Great (3rd Cent. CE)

Barbara Crostini, Uppsala

10:10-10:45

Libanios’ “Oration in Praise of Antioch” and the Seleukids

Simone Rendina, Cassino

10:45–11:00

Coffee & Tea Break

Panel III: Remembering the Seleukids in Post-Seleukid Dynasties: Individual Case Studies

Panel chair: Milinda Hoo

11:00–11:35

Inheriting Empire: The Parthian Reception of the Seleukid Legacy

Kateryna Baulina, Kyiv

11:35–12:10

The Seleukid Legacy in Palmyrene Royal Propaganda

Adam Attar, Amsterdam

12:10–12:45 Additional Paper for Panel VIII: The Seleukids in 21st-Century Video Games (Fr. afternoon)

Representation and Games: Introducing the EDR Circle of Ludic Communication to Seleukid Video Games.

Tirreg Verburg MA, Utrecht

12:45-14:00

Lunch Break

Special event: A selection of Seleukid-relateted Medieval manuscripts from the Universities Special Collection will be on display, details to be announced.

Panel IV: Remembering the Seleukids in Post-Seleukid Dynasties: Wider Perspectives

Panel chair: Rolf Strootma

14:00-14:35

Continuity, Cancellation, or Re-Introduction of the Seleukid Era in Near-Eastern Communities?

Altay Coşkun, Waterloo, ON

14:35-15:10

The Memory of the Seleukids in the Literary and Cultural Traditions of the Late Antique and Medieval Near East

Raúl Navas-Moreno, Barcelona

15:10-15:45

Damned Tyrants? Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh and the Afterlife of the Seleukid Royal Image in Iran

Richard Wenghofer, North Bay

15:45–16:00

Coffee & Tea Break

Panel V: Jewish and Christian Representations of the Seleukids

Panel chair: Altay Coşkun, Waterloo, ON

16:00–16:35

The Crystal Coffin of Daniel: Neoplatonic, Early Christian and Jewish Responses to Daniel’s Vision of the Succession of Empires

Ben Scolnic, Hamden, CT

16:35-17:10

Seleukids in the Epsilon Alexander Romance

Ory Amitay, Haifa

17:10-17:45

‘“The Evil Greeks”: The Seleukids in Modern National Jewish and Israeli Culture’

Eran Almagor, Jerusalem

Friday 14 November

Panel VI: Afterlife of Seleukid Coinage

Panel chair: Eva Anagnostou-Laoutides

09:00–09:35

An Elephantine Legacy: Elephants as a Seleukid Symbol and Its Reception in Antiquity and the Present

Angus Llewellyn Jacobson, Tasmania

09:35–10:10

Antiochus in Avalon: A Discussion of Seleukid Coinage in Britain

Jason Lundock, Winter Park, FL

10:10–10:45

Engraving History: Seleukid Coins in 17th Century Dutch Literature

Pim Möhring, Amsterdam

10:45–11:00

Coffee Break

Panel VII: Seleukid Fiction, 18th–20th Centuries

Panel chair: Koen Vacano, Utrecht University

11:00–11:35

Mediocre King, Tragic Hero: Georg Friedrich Händel’s Alexander Balus

Silke Knippschild, Bristol

11:35–12:10

A Century of Singing Seleukids (18th–19th Cents.)

Hein van Eekert, Almere, Flevoland

12:10–12:45

The Seleukid “East” in Fritz Leiber’s Fantasy Novella Adept’s Gambit (1947)

Rolf Strootman, Utrecht

12:45-13:45

Lunch Break

Panel VIII: The Seleukids in 21st-Century Video Games

Panel chair: Pim Möhring

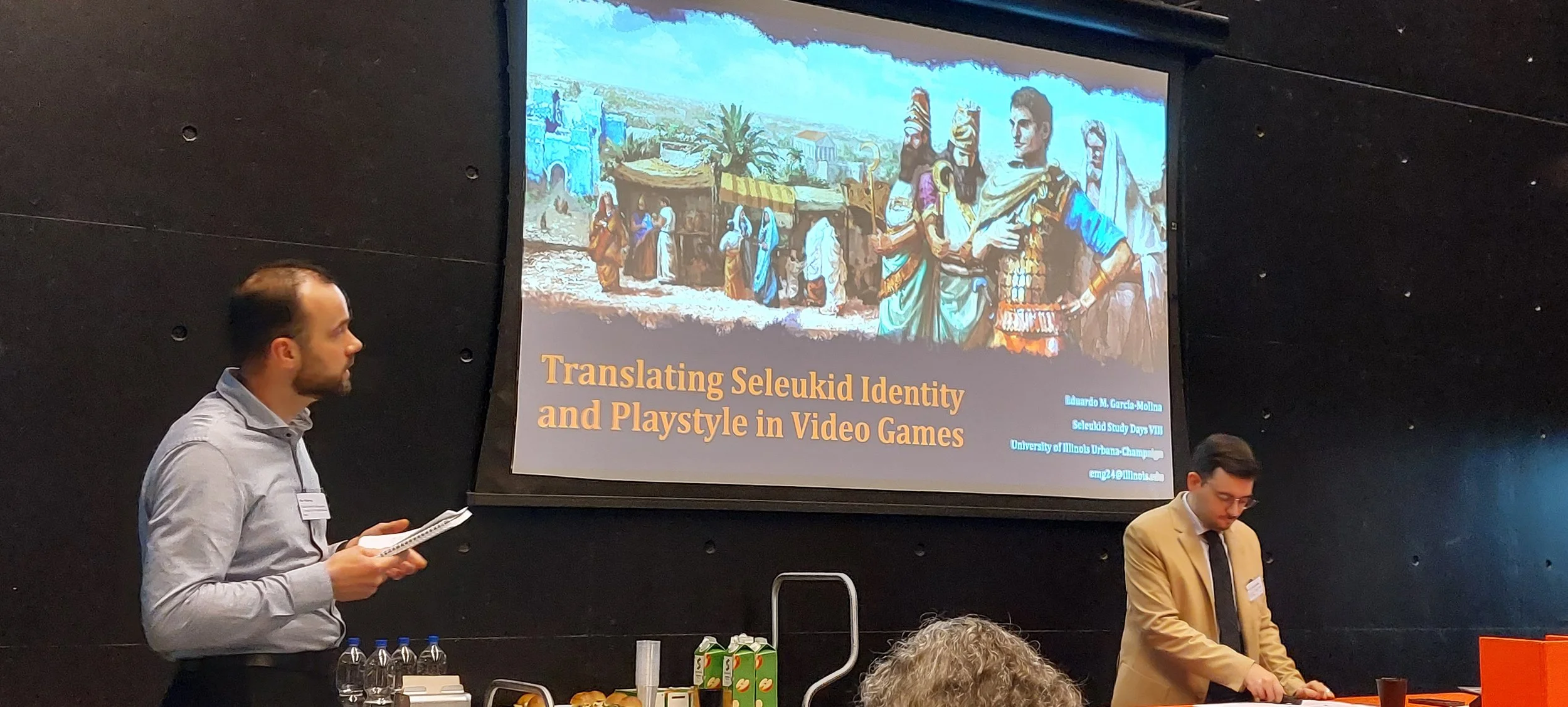

13:45–14:20

Rendering Seleukid Identity and Playstyle in Video Games

Eduardo García-Molina, Champaign, IL

14:20–14:55

‘Ahistoricity’, ‘Authenticity’, and ‘Accuracy’: Contested Seleukid Representation in Creative Assembly’s Total War Videogames

Daniel Hunter, New Brunswick, NJ

14:55–15:30

‘Orientalizing the Seleukids in Grand Strategy Video Games’

Jasmin Lukkari, Helsinki & Milan

15:30-16:00 Concluding Discussion: on Seleukid Reception

Afternoon: walk through the Old Town

20:00-23:00

Creative Dinner (place tba), including

‘An Epicurean Philosopher in the Seleukid Court: Two Letters from Philonides of Laodikeia about Kings He Knew Well’

Ben Scolnic, Hamden, CT‘The Bull-Horned King’

Angus Llewellyn Jacobson MA, The University of TasmaniaReading from the Seleukid novel ‘The Two Suns’

David Engels, VendéeSaturday, 15 November

As of 10 am: Social & cultural events

Gathering point will be the Domplein (Place before the Cathedral) for a visit to the adjacent 14th-century Pandhof. This will be followed by a visit of the nearby Catharijne Convent.

-

Dr. Eran Almagor, Jerusalem

“The Evil Greeks”: The Seleukids in Modern National Jewish and Israeli Culture

The Jewish festival Hanukah has assumed different appearances through the ages. It commemorated the Hasmoneans’ fight against Antiochos Epiphanes’ measures aimed to curtail Jewish religious practices, and their ensuing achievements. Yet, its initial political-national dimensions were intentionally suppressed throughout Jewish history in favour of a religious interpretation of the events. Hanukah thus came to celebrate the Temple’s rededication (164 BCE). The festival’s political and secular significance resurfaced, however, in the modern Jewish national movement from mid-19th century. The establishment of the state of Israel brought about further changes to the festival’s character. All these transformations reflected upon the representations of the Seleukids and their rule.

This paper aims to explore these representations and their main features in the modern era. Prominent among these images are the portrayal of the Seleukids as Greeks and their perceived nature as western imperialists who tried to impose their pagan religion and cosmopolitan attitude on the local Jewish population. Reference will also be given to some contemporary analogies made between the image of Seleukid religious persecution and the Holocaust.

The corpora for the paper include works of art and literature, essays from different parts of the political spectrum of the national Jewish movement (i.e., Socialist, Revisionist, or religious writers), popular images, children’s books, notable Hanukah songs, and even exchanges in the Israeli parliament from four years ago. This paper will not ignore the interrelation of these present-day images to the ancient Jewish sources, bearing in mind Hanukah’s motto “In those days at this time”.

Eran Almagor is the author of studies on Plutarch and other Greek writers of the Roman imperial period (Strabo, Josephus). His interests include Hellenistic history, the history of the Achaemenid Empire and its image in Greek literature (especially in Herodotos and Ktesias), Plutarch’s works (mainly the Lives), and the modern reception of Antiquity, particularly in popular culture. He is the author of Plutarch and the Persica (Edinburgh University Press, 2018), and is co-editor of Ancient Ethnography: New Approaches (Bloomsbury, 2013) and The Reception of Ancient Virtues and Vices in Modern Popular Culture (Brill, 2017).

Dr. Ory Amitay, School of Area and Historical Studies, University of Haifa

Seleukids in the Epsilon Alexander Romance

In my paper I offer to examine the role of two secondary characters in the epsilon recension of the Alexander Romance (AR). This recension (9th cent. CE), a distant outlier of the mainstream AR tradition, gives place of pride to one Seleukos and one Antiochos. These two characters are Alexander’s closest confidants and leading generals; they found cities in their own name, act as proxies for Alexander and are even mistakenly thought by others to be him. Since neither name is prominent in Alexander’s history, nor in the mainstream AR, their celebration in epsilon calls for interpretation.

I suggest that a main source used by the composer of epsilon was a hitherto unknown work, coming from the Seleukid realm. In this work, which I call the Seleukid Romance, Alexander and his two unmistakably Seleukid friends represent the interests of the Seleukid dynasty as a whole. Furthermore, the unique and clearly fictional geography ascribed to Alexander in epsilon mirrors the famous anabasis of Antiochos III and his consequent conquest of the southern Levant in the Fifth Syrian War.

A further point of interest is the inclusion of a story about Alexander in Jerusalem, which I argue is the earliest written version of this tradition. In addition, epsilon shows Alexander’s growing interest in the god of the Judeans, to the point of adopting monotheism. The work even pits Alexander and Seleukos vs. Gog and Magog. Consequently, I suggest that the Seleukid Romance was written by a Judaean and represents both the acceptability (even popularity) of early Seleukid rule in Jerusalem, and a putative Judaean vision for a future close bond between the Seleukid dynasty and the god of Judaea.

Ory Amitay BA, MA: Tel Aviv University; History; 1992–98

PhD: University of California, Berkeley; Graduate Group in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology; 1997–2002.

Since 2003, at the University of Haifa, I have taught survey courses on the ancient west and on the classical world; and topical courses on Greek history (Archaic to Hellenistic), Roman history (early republic; early and high empire), Judean history (second temple and beyond), myth and history, and Alexander the Great. In 2017–2022 I headed the university’s honors program.

My more recent publications include:

Books:

2010. From Alexander to Jesus. Berkeley.

2025. Alexander the Great in Jerusalem: Myth and History. Oxford.

Articles:

2011. “Procopius of Caesarea and the Girgashite Diaspora”, Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha 20: 257–276.

2011. “Kleodemos Malchos and the Origins of Africa”, Mouseion 11: 191–219.

2012. “Alexander in Bavli Tamid: in Search of a Meaning”, in (eds.) R. Stoneman, K. Erickson, I. Netton, The Alexander Romance in Persia and the East. Groningen. pp. 349–65.

2013. “The Correspondence in I Maccabees and the Possible Origins of the Judeo-Spartan Connection”. Scripta Classica Israelica 32: 79–105.

2014. “Josephus, Paulina and Fulvia: Hidden Agenda in Josephus, Antiquities 18.65–84”. The Ancient World 45: 101–21.

2014. “Vagantibus Graeciae Fabulis: The North African Wanderings of Antaios and Herakles”, Mediterranean Historical Review 29: 1–28.

With Kaye, Noah. 2015. “Kleopatra’s Dowry and the Historicity of AJ 12.154–55”, Historia 64.2: 131–155.

2017. “Dionysos in Jerusalem and the Historicity of 2Mac 6:7”, Harvard Theological Review 110: 265–279.

2018. “Alexander and Caligula in the Jerusalem Temple: A Case of Conflated Traditions”, in K. Nawotka, R. Rollinger, J. Wiesehöfer. A. Wojciechowska (eds.), The Historiography of Alexander the Great. Wiesbaden. 177–187.

2022. “Alexander in Ancient Jewish Literature”, in Stoneman, R. Alexander the Great in World Litearture. Cambridge, 109–142.

2023. “Alexander between Rome and Carthage in the Alexander Romance (A)”, Phoenix 77: 23–42.

Dr. Eva Anagnostou-Laoutides, Macquarie University

The Anecdotal History of the Seleukids in the Second and Third Centuries CE

The literary sources on the Seleukids are notoriously ‘scant and uneven’ (Strootman 2013, 6119), although more recently they have been studied with renewed zeal to draw attention to the engagement of the dynasty both with local traditions (Ogden 2017; Anagnostou-Laoutides 2022a/b, 2023) and with other Hellenistic dynasties (Visscher 2020; Fischer-Bovet 2021). Equally, Seleukid queens are increasingly recognized in scholarship for their important role as active agents in crafting and pursuing royal policies (Coşkun and McAuley 2016). Following on from this encouraging trend, my paper will focus on our least credible sources for Seleukid kings and queens, that is Lucian of Samosata and Athenaeus of Naucratis.

Lucian’s satirical dialogues, including his On the Syrian Goddess, Icaromenippus, and others) contain references to the first dynasty of the Seleukids, notably to queen Stratonike and her scandalous love-affair with Antiochos I, while in his Deipnosophistai, especially books 5 and 7, Athenaios portrays the Seleukids as generous patrons of letters and art and convivial banqueters, though never far from sympotic decadence and clandestine court politics. So far, these works have been cited as evidence for the history of the Seleukids and their efforts to establish their dynastic legitimacy. My paper, however, seeks to understand the reception of the Seleukids in the context of the second century and from the perspective of the audiences that Lucian and Athenaeus address. I claim that, despite the comical exaggeration of both works, Lucian and Athenaios present the Seleukids as typical monarchs who inspired the Romans in developing their own model of the benevolent emperor, always to be sniggered at, always to be feared.

Indicative Bibliography

Anagnostou-Laoutides, E. 2023. “The king-ship of the Seleucids: A Different Explanation of the Anchor Symbol”, in A. Coşkun and R. Wenghofer (eds), Seleukid Ideology – Reception, Response and Rejection, Stuttgart, 61–92.

Anagnostou-Laoutides, E. 2022a. “Heracles and Dumuzi: The Soteriological Aspects of Kingship under the Seleucids”, in G. Lenzo, M. Pellet, C. Nihan (eds), Les cultes aux rois et au héros dans l’Antiquité: continuité et changements à l’époque hellénistique, Tübingen, 241–274.

Anagnostou-Laoutides, E. 2022b. “Flexing Mythologies in Babylon and Antioch-on-the-Orontes: Divine Champions and their Aquatic Enemies under the Early Seleukids”, in E. Anagnostou-Laoutides and S. Pfeiffer (eds), Culture and Ideology under the Seleucids: Unframing a Dynasty, Leiden, 227–250.

Coşkun, A. and McAuley, A, 2016. Seleukid Royal Women: Creation, Representation and Distortion of Hellenistic Queenship in the Seleukid Empire. Stuttgart.

Fischer-Bovet, C., von Reden, S. 2021. Comparing the Ptolemaic and Seleucid Empires: Interaction, Communication and Resistance. Cambridge.

Ogden, D. 2017. The Legend of Seleucus: Kingship, Narrative and Mythmaking in the Ancient World. Cambridge.

Strootman, R. 2013. “Seleucids”, in R.S. Bagnall et al. (eds), The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, Malden, MA, 6119–6125.

Visscher, M.S. 2020. Beyond Alexandria: literature and empire in the Seleucid world. Oxford.

Eva Anagnostou-Laoutides is Associate Professor at the Department of History and Archaeology, Macquarie University, Sydney. She was a Future Fellow of the Australian Research Council (2017–2022), while she currently leads an Australian Research Council Discovery Project on the Crises of Leadership in the Eastern Roman Empire (250-1000 CE). Her research focuses on the use of mythic and religious traditions in the Hellenistic and Augustan periods, as well as the reception of Greek philosophy in Christianity. She is the author of Eros and Ritual (Gorgias, 2005 and 2013) and In the Garden of the Gods (Routledge, 2017), and co-editor of several volumes, including Eastern Christianity and Late Antique Philosophy (Brill, 2020) and Later Platonists and Their Heirs (Brill, 2023). She just completed a monograph on The History of Inebriation from Plato to Landino and is working on another book on Sexuality in Greek Epigrams and Later European Literature.

Adam Attar MA, Amsterdam

The Seleukid Legacy in Palmyrene Royal Propaganda

Unlike Egypt or Iran, the Levant is rarely treated as an ancient political entity due to the many languages, identities and ancient city-states that failed to establish a unified political system encompassing the region. As such, most scholars find it difficult to contextualize the Palmyrene royal claims during the third century crisis as anything but an attempt at the Roman throne or simply an opportunistic move by ambitious rich regional leaders. In this paper, I argue that the Levant became a loosely unified kingdom during the late-Seleukid period following the loss of Mesopotamia and the death of Antiochos VII. The dynasty’s eventual confinement to the Levant led to the emergence of a political identity shared by the inhabitants of Syria. This was solidified by the initial Roman treatment of most of the Levant as a province of Syria as inherited from the Seleukids. When examined against this background, the Palmyrene royal claims in 260 CE are clearly a continuation of the Seleukid claim to Syria. By integrating local primary sources showing Seleukid motives and lasting memory, I argue that Odainathos and his wife Zenobia attempted to utilize the Seleukids’ legitimacy as founders of the kingdom of Syria to support their own claim as the new founders of a Levantine kingdom. Instead of merely aiming at Rome’s throne, Odainathos sought to rule Syria as the legitimate successor of Seleukos I and Zenobia attempted the same policy before eventually challenging Aurelian as Augusta when the Roman invasion became inevitable.

CV

- History, Universiteit Utrecht 2017-2020: Bachelor program. I focused during my second and third years on the ancient history of the Near East, especially cultural exchange and the emergence of hybrid identities.

- Ancient, Medieval, and Renaissance Studies, Universiteit Utrecht 2020-2022: Research master program. I built upon my research during my bachelor and focused more on ancient cultural exchange especially during the Hellenistic period in the Levant and how diversity was a positive source of social cohesion.

- Leraar Geschiedenis, Universiteit van Amsterdam 2022-2023: Master program focused on pedagogy and the strategies of teaching history.

Kateryna Baulina, PhD student, Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv

Inheriting Empire: The Parthian Reception of the Seleukid Legacy

The Parthian Empire, which rose on the Iranian plateau, inherited a complex and multifaceted legacy from the Seleukids. This abstract examines how the Parthians engaged with and reinterpreted their Seleukid predecessors’ cultural and political heritage in a dynamic and evolving manner. Instead of a static replacement, the Parthians were involved in selective adoption, adaptation, and rejection of elements of Seleukid traditions, forging their own distinct identity while simultaneously legitimizing their rule. This paper will explore the nuanced interplay between continuity and change by analyzing various aspects of Parthian society, including art and architecture, religious practices, and royal ideology. By examining how the Parthians utilized and reframed Seleukid symbols of power, administrative structures, and cultural expressions, we can better understand the processes of cultural transmission and identity formation in the ancient world. The Parthian relationship with the Seleukid past was not simply one of conquest and replacement but a dynamic transformation process. I will show how the Parthians utilized Seleukid architectural styles and even royal iconography to legitimize their rule and construct a new Iranian identity. This paper will demonstrate that the Parthian reception of the Seleukid legacy was not a simple act of imitation but rather a dynamic process of re-contextualization, ultimately contributing to the unique character of the Parthian Empire.

Kateryna Baulina is a PhD student from Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv (Ukraine). Her PhD research is on the evolution of the titulary of Hephaestion as a manifestation of the syncretism of the Ancient Near Eastern political Traditions in the Empire of Alexander the Great. She holds an MA and BA degree in Ancient History from the same university. Kateryna is the only Ukrainian researcher specializing in Assyrian and Achaemenid imperial history, covering court rituals, titulature, and sacral kingship.

She is the author of: “Hof und Hofgesellschaft” Das achaimenidisch-persische Imperium (Wiesbaden 2025); “Interpretation of the Palace Ceremony “Proskynesis”, as a Sacral Element in the Court of the Achaemenid (Leuven/Paris/Bristol 2023); “Reflection of Hephaestion’s Divinity” (Kyiv 2022).

Dr. Altay Coşkun, University of Waterloo

Continuity, Cancellation, or Re-Introduction of the Seleukid Era in Near-Eastern Communities?

The Seleukids were the first Hellenistic kings to establish a time count for their whole dynasty rather than for their individual rulers. Soon after taking the diadem in 305 BCE, Seleukos I made his arrival in Babylon on 1 Nisan 311 BCE the start point of his regnal years. When his son Antiochos I became sole ruler, he chose not to change to a new count with his appointment as co-ruling king in 296 BCE or with his father’s death in 281 BCE but to continue the latter’s count. With minor variation (1 SEM = 312/11 BCE and 1 SEB = 311/10 BCE), this ‘Seleukid Era’ lived on through the next centuries. A maximalist view regards this innovation as a bold step of appropriating time and space with the dynasty’s ideology (Kosmin, P.J. 2018: Time and Its Adversaries in the Seleucid Empire, Cambridge, MA), whereas a minimalist view may emphasize the initial predominance of pragmatic choices and a slow spread of this new year count.

The present paper aims at studying the diverse reactions of local communities or rulers while or after gaining independence from Seleukid rule: was the era maintained to express an affiliation with the erstwhile most powerful kingdom in the region or was it hastily rejected to yield to different sources of authority. We should assume that responses in complex settings of social, political, and cultural relations were pragmatic and experimental. The evidence for the transitional years is admittedly scarce except for Judaea. The high density of Seleukid Era dates in 1 and 2 Maccabees, combined with the long way to permanent independence makes it the ideal study ground for our purposes. The lessons learnt may also help us shed light on the less well attested cases. We should hypothesize that there may well have been less continuity and more of a back and forth, such as in Arsakid Parthia and perhaps also in Palmyra. We should, however, exclude Bithynia and Pontos, as they had established dynastic kingdoms even before the Seleukid Era had been conceived, and there is no indication that they ever adopted the Seleukid Era.

Altay Coşkun is Professor of Classical Studies at the University of Waterloo, ON. His appointment in 2009 followed his PhD (1999) and Habilitation (2007), both at Trier University. He held various research positions at Oxford, Trier & Exeter. His interests range from Greek colonialism to the Hellenistic kingdoms, as well as from Roman diplomacy and citizenship studies to Late Roman legislation and poetry. His latest publications include Seleukid Royal Women (co-edited with Alex McAuley, 2016), Rome and the Seleukid East (co-edited with David Engels, 2019), Ethnic Constructs, Royal Dynasties and Historical Geography around the Black Sea Littoral (2021), Galatian Victories and Other Studies into the Agency and Identity of the Galatians in the Hellenistic and Early-Roman Periods (2022), Seleukid Ideology: Creation, Reception and Response (co-edited with Richard Wenghofer, 2023), The Seleukids at War: Recruitment, Composition, and Organization (co-edited with Ben Scolnic, 2024), and (De-) Constructing the Seleukids: Queens, Co-Ruling Kings, and King Lists (ca. 2025). Together with Ben Scolnic, he runs the Seleukid Lecture Series (since 2021: http://www.altaycoskun.com/seleukid-lectures) as well as Unheard Voices of the Past (since 2022: http://www.altaycoskun.com/welcome-to-the-unheard-voices), besides editing the book series Seleukid Perspectives.

Dr. Barbara Crostini, Senior Lecturer in Church History, Art History and Cultural Studies at the Newman Institute, Uppsala

A Cosmopolitan City: Governing Roman Dura Europos through Myths of Seleukos and Alexander the Great (3rd Cent. CE)

Recent scholarship has highlighted the intercultural and interreligious character of the inhabitants of the Roman border-town of Dura Europos on the Euphrates (Kaizer, Jensen). This situation has been presented as a self-evident consequence of the geopolitical placement of the city at the crossroads between empires. In this paper, I consider a more active role of Dura Europos’ citizens and Roman governors in promoting a culture that cut across ethnic, religious, and even gender differences through an appeal to basic common ideals and human aspirations. The cohesion sought thus valued not so much the production of a hybrid culture, but the harmony in difference that could unite different peoples into one political body through shared ideals. This project was both inspired and carried out by the Severans through appeal to Alexander the Great as a cult figure.

The claim that Dura was founded by Seleukos Nikator, the traces of a cult of the Seleukid king, and markers of Alexander’s memory – since Dura was located near the place of Alexander’s mythical death – conspire to create the impression of the town as a privileged place for the reception of the Seleukid-Alexandrian ideals of a cosmopolitan society, realized in practice in the convergence of different cultures at Dura Europos. Further, the performative character of the city suggests that it was a probable seedbed of popular narratives that functioned both as entertainment and as catechetical demonstrations of the Greco-Roman intercultural ideal.

Barbara Crostini is Senior Lecturer in Church History, Art History and Cultural Studies at the Newman Institute, Uppsala, and Adjunct Professor in Greek at the Department of Linguistics and Philology in Uppsala University. She has earned national qualifications from the Italian Ministero per l’Università e la Ricerca (MUR) as Associate Professor in History of Religions, History of the Book, and Greek Philology. Her interests range from Late Antiquity to the Byzantine Middle Ages and her publications focus on both texts and material culture, especially Greek manuscripts. She has recently edited several collections of essays, among which are Syrian Stylites: Rereadings and Recastings of Late Ancient Superheroes, co-edited with Christian Høgel, Transactions of the Swedish Research Institute in Istanbul, 26 (Istanbul: Swedish Research Institute, 2024); Why We Sing: Music, Word and Liturgy in Early Christianity, in Honour of Anders Ekenberg, co-edited with Carl-Johan Berglund and James Kelhoffer (Leiden: Brill, 2023); Receptions of the Bible in Byzantium: Texts, Manuscripts, and Their Readers, co-edited with Reinhart Ceulemans, Studia Byzantina Upsaliensia 20 (Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, 2021). She is working on a book about Dura Europos as a theatrical city.

Dr. David Engels, Lecturer at the Catholic University in Vendée (ICES)

He will read from his Seleukid novel "The Two Suns"

The novel opens when the young Antiochos, son of Seleukos I Nikator and the Iranian princess Apama, rides eastward for the first time to take command of the Upper Satrapies. He is thirty, newly married, proud, and uneasy—an heir sent from the opulent court of Babylon into the unbounded silence of the Iranian highlands. His escort is a moving emblem of the empire: Macedonian veterans, Persian nobles, Aramaean mule-drivers, and a few wordless Indians from Alexander’s half-forgotten armies. Among them, Antiochos senses not unity but Babel. At dusk, beside a ruined roadside shrine, he encounters a Gymnosophist, a naked philosopher who claims to have spoken with Alexander. Their brief dialogue becomes the axis of Antiochos’s fate. The sage draws two circles in the dust and tells him, “One sun burns the world, one burns itself. Between them stand the kings.” The riddle unsettles the prince, lingering after the man vanishes into the dark. As dawn breaks, the heat-mirage doubles the rising sun. Antiochos feels both fear and exaltation. He is leaving adolescence and certainty behind, riding toward the fire that will one day consume him—the first step in a life spent forever between two suns.

David Engels is a Belgian historian specialised in the fields of Roman religion, the Seleukid Empire and intercultural comparatism. Engels gained his PhD at the RWTH-Aachen with a study on Roman divination ("Das römische Vorzeichenwesen", Stuttgart, Steiner, 2007) and became professor and chair for Roman History in 2008 at the “Free University of Brussels” (ULB), where he also worked as editor-in-chief and director of the journal "Latomus - revue d'études latines". During these years, beside numerous edited volumes, monographs and articles, he published his habilitation equivalence, called "Studies in the Seleukid Empire between East and West" (Leuven, Peeters, 2017). From 2018 to 2024, Engels worked as "Senior Analyst" at the “Instytut Zachodni” in Poznań in Poland, and since 2022, he is also lecturer for world history and compared civilisational studies at the Catholic University in Vendée (ICES). Beside the above-mentioned monograph on Seleukid history and numerous scholarly papers, Engels co-edited, with Altay Coskun, the volume "Rome and the Seleukid East" (Brussels, Latomus, 2019) and co-wrote, together with Chiara Grigolin, the edition, translation and commentary of the fragments of Pausanias of Antioch, published in the newest volume of the "Fragmente der Griechischen Historiker" (IV.E.4, Leiden, Brill, 2025) which Engels co-edited with Stefan Schorn.

Dr. Eduardo García-Molina, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

Rendering Seleukid Identity and Playstyle in Video Games

Like Seleukid Studies, Game Studies has enjoyed an uptick in activity over the past two decades that has produced numerous works on the reception of the ancient world within virtual ones (Reinhard 2018; Rollinger 2020; Draycott and Cook 2022). This presentation synthesizes these two strands to explore how game designers have rendered the governance, material culture, and identity of the Seleukid Empire within strategy games like Rome: Total WarI & II (2004, 2013), Field of Glory: Empires (2019), Imperator: Rome (2019), and Old World (2022). It is particularly interested in the adaptation of Seleukid identity explored by scholarship (Anagnostou-Laoutides and Pfeiffer 2022; Coşkun and Wenghofer 2023) into game mechanics that encourage players to govern a multicultural empire by granting them a diverse military roster and bonuses for managing a heterogenous population; such a playstyle often clashes with mechanics that reward players for creating an empire that is culturally monolithic (i.e., ‘Hellenic’, ‘Roman’, ‘Eastern’). The Seleukids are thus presented to players as a faction uniquely suited to develop a culturally composite empire.

These Seleukid traits, however, still operate within an overarching ludic framework that relies on modern rules and assumptions on imperialism and ‘strong’ states (i.e., actively converting populations to a singular imperial religion) that often clash with actual ancient practices (Mukherjee 2017, García-Molina forthcoming). The second portion of this presentation fixates on this dissonance in the behavior of virtual and ancient empires, and how the Seleukid Empire is translated within the largest medium of its modern reception: video games.

Initial Bibliography

Anagnostou-Laoutides, Eva and Pfeiffer, Stefan (eds.) 2022. Culture and Ideology under the Seleucids: Unframing a Dynasty. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Coşkun, Altay and Wenghofer, Richard (eds.) 2023. Seleukid Ideology: Creation, Reception and Response. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag.

Draycott, Jane and Cook, Kate (eds.) 2022. Women in Classical Video Games. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

García-Molina, Eduardo. forthcoming. “Culture, Population, and the Simulation of Ancient State Power in Total War.” In Dor, Simon (ed.) Depictions of Power: Strategy and Management Games. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Mukherjee, Souvik. 2017. Videogames and Postcolonialism: Empire Plays Back. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Reinhard, Andrew. 2018. Archaeogaming: An Introduction to Archaeology in and of Video Games. New York: Berghahn Books.

Rollinger, Christian (ed.) 2020. Classical Antiquity in Video Games: Playing with the Ancient World. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Ludography

Rome: Total War (2004) Creative Assembly/Activision, PC.

Total War: Rome II (2013) Creative Assembly/SEGA, PC.

Field of Glory: Empires (2019) Slitherine Software, PC.

Imperator: Rome (2019) Paradox Interactive, PC.

Old World (2022) Mohawk Games, PC.

CV

I am currently a Postdoctoral Research Associate and, at the end of this academic year an Assistant Professor, in the Classics Department and Humanities Research Institute at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign after finishing my dissertation, Archival Information and the Ordering of the Seleukid State, at the University of Chicago in 2024. My primary area of research centers on exploring ancient subjects’ experiences with the administration of the Seleukid Empire. My dissertation contributed to this conversation by exploring the role that archives and documents had in shaping recordkeeping protocols and consequently how bureaucracy and documents come to define the empire for subjects. This extends to the legal realm by emphasizing that material conditions set by the state (i.e., the production and archiving of Greek contracts in parchment or papyrus) affect notions of legality at both a local and central level.

I have contributed to volumes on subjects like Seleukeia Pieria, the translation of state behaviors within gaming simulations, and generally on Hellenistic armies. Currently I am writing my first monograph based on my dissertation in addition to articles on Seleukid recordkeeping, cases of impiety within the empire, and the social dimensions of participation in the Seleukid army.

Yanxiao He

Imagining the Seleukid Past in Late Roman Antioch: Intellectuals in the Face of Popular Power

Julian’s 363 speech Misopogon has garnered significant attention, whether for price controls (Elm 2012, 327–335; Marvin 2023, 286–326) or mass and elite communication in Antioch (Gleason 1986, 106–119; Van Hoof and Van Nuffeln 2011, 116–184. However, a notable gap is Julian’s critique of Antioch’s obsession with pantomime, particularly his invocation of the Antiochos story to illustrate sexual indulgence as foundational to Antioch (Jul. Mis. 348B), with transgender implications in pantomime (cf. Webb 2008). This paper examines the reception of the Seleukids in late Roman Antioch through the lens of mass and elite interaction, focusing on pantomime critique.

First, in connection with Galen’s similar use of a medical case – where a Roman matron suffers lovesickness for a pantomime dancer as a metaphor for Rome’s illness (Praen. 6) – I consider Misopogon as a continuation of intellectual critiques of pantomime dance (cf. Lada-Richards 2007). Second, I analyze Libanios’ Oration 16 consoling Antioch after Misopogon was made public. By reflecting on Libanios’ balanced stance in preventing mass riots by closing theatres, I explore his nuanced engagement with pantomime. This includes his previous positive assessment of pantomime as part of Syrian identity in Oration 64 and his evocation of the Hellenistic past in Oration 11, which reflect a compromise with popular ideology in Antioch (cf. Brown 1992), while Libanios hints at it in his autobiography (Lib. Or. 1.86). I thus argue that Julian and Libanios confirm Lucian’s mention of the Antiochos story as a pantomime narrative in Syria-Phoenicia (Luc. De Salt. 58f.; Swain 1992, 76–82).

Bibliography

Brown, P. (1992): Power and Persuasion in Late Antiquity: Towards a Christian Empire (Madison, WI.)

Elm, S. (2012): Sons of Hellenism, Fathers of the Church: Emperor Julian, Gregory of Nazianzus, and the Vision of Rome (Berkeley).

Gleason M. (1986): “Festive Satire: Julian’s Misopogon and the New Year at Antioch”, JRS (76): 106–19.

Lada-Richards, I. (2007): Silent Eloquence. Lucian and Pantomime Dancing (London).

Marvin, J. (2023): “Julian’s Misopogon and the Food Shortage in Antioch: Imperial Criticism of Community Response”, SLA (7)2: 286-326.

Swain, S. (1992): “Novel and Pantomime in Plutarch's 'Antony'”, Hermes (120): 76-82.

Van Hoof, Lieve and Van Nuffeln, P. (2011): “Monarchy and Mass Communication: Antioch A.D. 362/3 Revisited”, JRS (101): 166-84.

Webb, R. (2008): Demons and Dancers in Late Antiquity (Cambridge, MA).

Yanxiao He (he/him) received his PhD from the University of Chicago. He is now the Shuimu Post-doc Research Fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study in Humanities and Social Sciences at Tsinghua University in Beijing. His research revolves around the Hellenistic and Roman East, Greek novels and Roman pantomime, and classical receptions in East Asian popular culture. He is currently completing a book manuscript titled The Performance Road: Theatricality and Ethnography in Long Hellenistic Asia. His English writings appeared or will appear in the American Journal of Philology, Classical Quarterly, Classical World, Classical Receptions Journal, and Chinese Studies in History. By working with the Shanghai Review of Books, he has been actively introducing updated anglophone scholarship on Classics to Chinese audiences, from the Postclassicisms volume in 2020 to TAPA's recent Race and Racism volume in 2024. He was an official working staff for the 2024 World Conference of Classics in Beijing, which involved inviting and hosting international guests. His scholarship has been recognized by the John J. Winkler Memorial Prize and the Erich S. Gruen Prize.

Daniel Hunter

‘Ahistoricity’, ‘Authenticity’, and ‘Accuracy’: Contested Seleukid Representation in Creative Assembly’s Total War Videogames

As the popularity of videogames set in classical antiquity increases amongst the public, scholarly interest in such products as ‘participatory mediums’ of history and as items of classical reception is on the rise (Chapman 2016; Hatlen 2013; Kokonis 2012; McCall 2018; Rollinger 2020). This paper examines the representations of the Seleukids in two entries in the Total War videogame series: namely 2004’s Rome: Total War and its 2013 sequel Total War: Rome II. In short, Seleukid representation differs drastically between the two entries, from a more ahistorical representation in the former game, largely presenting the Seleukids in 270 BCE as a strictly Graeco-Macedonian state limited to Syria and northern Mesopotamia, to a more ‘authentic’ representation in the latter which depicts the Seleukids in 272 BCE as ethnically diverse and extending political control, albeit indirectly through client states, further east beyond the Tigris (Brown 2013). Yet elements of both games’ audiences felt dissatisfied with this initial representation in both games, feeling that the developers deviated too far from historical accuracy. Three player-produced modifications, i.e. free downloadable content produced by members of the public to alter the experience of the game, will be considered. The three modifications which are examined are some of the most popular modifications and extensively alter the presentation of the Seleukids, such as by presenting direct Seleukid rule over its eastern territories and thereby presenting Seleukid power more accurately than presented in the original games (Europa Babarorum Team 2008; Philips 2018). The paper thus examines both the initial representation of the Seleukids by the games’ developers as well as the desire felt by select members of the games’ respective fanbases to participate in amending, modifying, and ‘correcting’ the initial representation of the Seleukids.

Select Bibliography

Brown, F. (2013) “Placing Authenticity over Accuracy in Total War: Rome II.” https://www.pcgamesn.com/totalwar/placing-authenticity-over-accuracy-total-war-rome-ii

Chapman, A. (2016). Digital Games as History: How Videogames Represent the Past and Offer Access to Historical Practice. Routledge.

Europa Babarorum Team. (2008) “Welcome and Mission Statement.“ Accessed via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://web.archive.org/web/20080214230528/http://www.europabarbarorum.com/

Hatlen, J. F. (2013) “Students of Rome: Total War.” Greek and Roman Games in the Computer Age. Thorsen, T. S. ed. TAPIR Akademisk Forlag.

Kokonis, M. (2012) “The Reader as Author and the Ontological Divide: Rome Total War and the Semiotic Process.” Gramma: Journal of Theory and Criticism 20, pp. 145-167.

McCall, J. (2018) “Videogames as Participatory Public History.” A Companion to Public History. Dean, D. ed. Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 405-416.

Philips, T. (2018) “Get out there and Mod – Don’t be Intimidated”: An Interview with the Divide et Impera Team.” https://www.totalwar.com/blog/an-interview-with-the-divide-et-impera-team/

Rollinger, C. (2020) “Prologue, Playing with the Ancient World: An Introduction to Classical Antiquity in Video Games.” Classical Antiquity in Video Games: Playing with the Ancient World. Rollinger, C. ed. Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 1-18.

CV

Education

PhD Candidate in Interdisciplinary Classics and Ancient History (Rutgers University – New Brunswick) September 2022 – Ongoing

Master of Arts in Languages & Cultures – Classics (Texas Tech University) August 2019 – May 2022

Master of Arts in Ancient History (University of Auckland) February 2017 – February 2019

Papers Presented at Conferences and Seminars

SCS Annual Meeting 2025 - Appian’s Narrative of the “Asiatic Vespers” and Comparison with Genocide Narratives in the earlier Judaeo-Christian Literary tradition

CAAS Annual Meeting 2024 - Oedipus, ἐνάργεια, and Aesthetics: The Extispicy in Seneca’s Oedipus

CAAS Annual Meeting 2023 - A Spectacle of Disgust:An Ekphrastic Reading of De Rerum Natura 6.1138-1286.

Culture and Ideology under the Seleucids: An Interdisciplinary Approach (Macquarie University), 29th – 31st March 2019 - The Influence of Seleucid Coinage upon the Bithynian and Pontic Monarchies to the reign of Mithridates VI.

Money and the Military in Antiquity (University of Auckland), 19th October 2018 - Pyrrhic Coins and Ideas of Hellenistic Kingship from 280 – 275 BCE.

Publication

Hunter, D. (2022) “The Influence of Seleukid Coinage upon the Bithynian and Pontic Monarchies to the Reign of Mithridates VI.” Culture and Ideology under the Seleukids: Unframing a Dynasty. Anagnostou-Laoutides, E. and Pfeiffer, S. eds. De Gruyter, pp. 269-296.

Dr. Silke Knippschild, University of Bristol

Mediocre King, Tragic Hero: Georg Friedrich Händel’s Alexander Balus

In the second century, the Seleukid Empire was in turmoil: the royal house split, usurpers afoot. One such pretender was young Alexander Balas, a man from nowhere who claimed to be related to Antiochos IV. Alexander was a staunch supporter of Jonathan, leader of Judaea. He was allied with and betrayed by Ptolemy, marrying his daughter Kleopatra, before her father handed her over to the next pretender. In 1748, Georg Friedrich Händel chose the hapless usurper as subject for a new oratorio, Alexander Balus. Unsurprisingly, the narrative thread of the work is the triumph of Judaism over paganism. However, Händel changed the story of Alexander’s life, turning him into a great king and devoted lover, betrayed by a pretender. Written shortly after the Jacobite uprising, this was an emotive theme. The motif of connubial bliss served as a counterpoint: falling in love, married happiness, and devastation when Kleopatra is kidnapped and Alexander murdered, all expressed in an unusual form of aria. Händel chose the blank page of Alexander’s life to turn a mediocre king into a tragic hero and vehicle for a moral message about betrayal and the power of love.

CV

Silke Knippschild is Senior Lecturer in Ancient History at the University of Bristol. Her main research interests lie in the field of intercultural relations and cross-cultural influences between the Ancient Near East, Greece and Rome. A further research focus is the reception of antiquity in the visual and performing arts. She is author of „Drum bietet zum Bunde die Hände“: Rechtssymbolische Akte in zwischenstaatlichen Beziehungen im altorientalischen und griechisch-römischen Altertum (2002) and co-editor of Imagines: La Antigüedad en las artes escénicas y visuales (2007), and of Seduction and Power: Antiquity in the Performing and Visual Arts, Imagines II (2013). Papers focussing on reception are, e.g., Homero abanderado. “Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria”, las mujeres, el libertinaje y la defensa de la fe en la Venecia de la Edad Moderna (2017); Woman on Top? Women's Suffrage and the Power of the “Oriental Woman” (2013), and El Prestigio del Pasado: La representación de la Antigüedad como signo del poder en la Inglaterra del Siglo XVII (2007).

Angus Llewellyn Jacobson MA, The University of Tasmania

Creative piece: The Bull-Horned King

This is an imagined dialogue between Antiochos I and his master painter Aineias that may give us an idea of how the bull-horned portrait of Seleukos I came into being.

Paper abstract: An Elephantine Legacy: Elephants as a Seleukid Symbol and Its Reception in Antiquity and the Present

On its release, the videogame Rome: Total War (2004)featured a diverse roster of playable factions, among them two of the dynasties which succeeded Alexander: Ptolemaic Egypt and the Seleukid Empire. While the former’s in-game symbol was an ankh, the latter’s was curiously a Korinthian helmet. In fact, only its use of ethnically-diverse combined arms and, importantly, elephants distinguished the faction as ‘Seleukid’. And understandably so. The Seleukid dynasts themselves had frequently employed both elephants in spectacles and pachydermic monetary iconography to symbolise their majesty and military might. So, it seems that Demetrios Poliorketes’ jibe that Seleukos I was more a ‘Master of the Elephants’ (ἐλεφαντάρχης) (Plut. Demetr. 25.4; cf. Athen. 6.261b = Phylarchos FGrH 81 F 31) than a king stuck. ‘To think Seleucid,’ as Kosmin aptly puts it, ‘is to see elephants’. (Kosmin 2014, 3). The present paper seeks to understand this mental connection, untangling the evolution of the Seleukid elephant’s symbology from antiquity to the present. It considers that: 1) while other Hellenistic dynasts also used these beasts, the Seleukids consciously shaped elephants into physical and metaphorical manifestations of their royal power, promoting the creatures’ centrality to their dynastic identity and legacy; 2) the dynasty’s enemies, such as Rome, would in turn exploit this association and inadvertently cement the synonymity of elephants and the Seleukids; and 3) the prominence and popularity of the Seleukid-elephant association in antiquity has fostered an inability in modern fiction, games, and other media to separate the species from the Seleukids.

CV

Angus Llewellyn Jacobson is an up-and-coming Australian Aboriginal scholar currently undertaking his PhD in Classics at the University of Tasmania. While his thesis focuses specifically on the Seleukid-Antigonid οἰκειότης as a mechanism of dynastic preservation and control from the Battle of Ipsos to Antigonos Gonatas’ death, he also possesses a profound interest in numismatics, Greek and Latin literature, royal/imperial ideologies, and Late Antiquity, particularly the reign of Julian. In 2022, he was the recipient of the distinguished Douglas Kelly Australian Essay Competition for his research on Seneca’s kingship model in the De clementia and its influence on later Roman authors (through ASCS). Already in his PhD’s first year, Angus has presented his research on Libanios’ Antiochikos and early Antigonid-Seleukid relations in the inaugural lecture of the Seleukid Lecture Series’ 8th edition. For 2025, he has been awarded the University of Tasmania’s Graduate Teaching Fellowship in Classics and the Near Eastern Archaeological Foundation’s Catherine Southwell-Keeley Travel Grant, which will enable him to undertake research on key artefacts and archaeological sites related to the Seleukid-Antigonid οἰκειότης in Türkiye.

Dr. Jasmin Lukkari, University of Helsinki & University of Milan

(Jasmin.Lukkari@helsinki.fi)

‘Orientalizing the Seleukids in Grand Strategy Video Games’

In this paper, I examine whether the orientalizing western perspective affects the representation of the Seleukids in four recent video games from the popular ‘grand strategy’ genre: Total War: Rome II (2013), Field of Glory 2 (2017), Field of Glory: Empires (2019) and Imperator: Rome (2019). These games focus on military conquest and are set during the expansion of the Roman Republic, featuring the Seleukid Empire as one of the many playable factions, among others such as Carthage, Macedon, and Rome of course. These games have been very popular, having sold millions of copies worldwide. It can be argued that today this genre of video games is the single most influential type of media that shape popular perceptions of antiquity.

These games were made by European game developers for mainly western audiences. In this paper I examine whether ancient eastern stereotypes affect the Seleukid representation in these games through a modern orientalizing filter. For example, Ancient Greek writers described Persians as lazy, feminine and weak soldiers. Roman writers adopted these same eastern stereotypes and generally applied them to all cultures in the Eastern Mediterranean (cf. Livy describing Seleukid men in this manner: 35.49.8, 36.11.1-6, 41.20.10–13). Europeans have continued perpetuating these common Orientalist tropes in modern times (cf. E. Said, Orientalism, 1978). Do these Romano-centric games continue this questionable tradition? I will find the answer to these questions by examining the visual, narrative and technical (game mechanics-wise) rendition of the Seleukid Empire compared to the other playable factions such as Rome.

Jasmin Lukkari is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Helsinki (Department of Department of Philosophy, History and Art Studies) and a visiting scholar at the University of Milan (Department of Literary Studies, Philology and Linguistics) for the academic year 2024—2025. In 2023, she obtained a PhD degree in History, jointly (cotutelle) from the University of Helsinki and the University of Cologne. Her thesis was titledExemplary Others – Virtus, Roman Identity, and Hellenistic Kings in Republican and Augustan Historical Narratives. Her current research focuses on Roman historiography, ancient historical narratives and their reception, and relations between the Roman Republic and the Hellenistic East.

Jason Lundock

Antiochus in Avalon: A Discussion of Seleukid Coinage in Britain

This paper addresses an unusual and unexpected phenomenon: the finding of coins of Seleukid manufacture in the plough soil of Britain and reported through the Portable Antiquities Scheme. The presence of these finds is anomalous not only as these coins are not expected to have been used in circulation during any period in the island’s history, but also that they appear to lack analogous finds from dated archaeological excavations; thus proving themselves worthy of special examination in their own right. After offering a site analysis on the locations where Seleukid coins have been found in Britain, comment will be made on the likely timeframe of import/use and deposition of the finds. This will then be used as a backdrop to discuss the possible reception of these coins as symbols of Seleukid cultural tradition/heritage to those who imported, appreciated and subsequently deposited these symbols of the ancient Hellenistic kingdom in the countryside of a location far from their land of origin.

Jason Lundock is Lecturer and Associate Course Director in the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences at Full Sail University Winter Park, Florida. He gained his BA (2009) and MA (2010) at King’s College London. The title of his MA thesis was “The Buzenol vallus relief: Analysis of Agrarian Iconography in Gallia Belgica”. He was awarded his PhD at Harvard University for his “Study of the Deposition and Distribution of Copper Alloy Vessels in Roman Britain” (2014). His recent publications include the co-ed. volume Water in the Roman World: Engineering, Trade, Religion and Daily Life (Archaeopress 2022); (with Aaron W. Irvin) ‘Purification through puppies: Dog symbolism and sacrifice in the Mediterranean world’, in A.W. Irvin (ed.), “Purification through Puppies”. Community and Identity at the Edges of the Classical World, 189-207 (Wiley Publications, 2021); ‘Rural Society on the Edge of Empire: Copper Alloy Vessels in Roman Britain Reported through the Portable Antiquities Scheme’, in Marko A. Janković and Vladimir D. Mihajlović (eds.), Imperialism and Identities on the Edges of the Roman World, vol. II, 51-84(Cambridge Scholars, 2018).

Ezequiel Martin Parra, University of Michigan (emparra@umich.edu)

Good father, better son: reframed kingship in Agustín Moreto’s comedy “Antíoco y Seleuco”

The story of Stratonike and Antiochos was a well-known literary motive in post-Renaissance Europe, but it had a limited reception in Spain up to the 19th century. A notable exception is Agustín Moreto's comedy of intrigue "Antíoco y Seleuco" (1676), a celebrated piece of Spanish Golden Age drama that displays Antiochos' arduous path to get his stepmother's hand in marriage. However, Moreto's version presents some variations concerning ancient sources and contemporary accounts circulating in the 17th century. This paper explores such variations, considering them the result of active interventions on the author's part rather than the consequence of centuries of transmission. While past scholarship has explained Moreto's particular version, arguing that he had to rework the traditional tale to escape censorship in ultra-Catholic Spain, I claim that the dramatist had his own political agenda, which he embedded in the text. The comedy insists on topics of filial/paternal piety, dynastic preservation, and kingly justice, all of which worked as a critique and exhortation to the Late Habsburgs monarchs in the context of an empire that faced an acute political crisis. Moreto crafted a paradigm of kingship in consonance with political ideas that circulated during his time, ideas to which he gave life in the form of characters of ancient days that confronted the same moral and political challenges faced by the Spanish crown.

CV

Ezequiel Martin Parra received his B.A. in History from the National University of Córdoba (Argentina). He is currently working on a dissertation on Diodorus Siculus’ conception of empire for his M.A. in Classical Studies at the University of Buenos Aires. He is part of the Ph.D. program in Ancient History at the University of Michigan. His publications have focused mainly on the Hellenistic Age, exploring the origins and meaning of said concept and of royal ideology in the Seleukid Empire.

Dr. Christian Michel, Heinrich-Heine-University Düsseldorf

Translatio imperii? Seleukids and Romans in book eight of the chronicle of Johannes Malalas

In the 8th book of his chronicle, Johannes Malalas offers a detailed if somewhat distorted narrative of the Hellenistic history from Alexander the Great to the death of Cleopatra and Marcus Antonius. The Seleukid kings feature most prominently in this section of the chronicle, that was compiled in the second half of the sixth century AD. Much attention is given to the suppression of the Maccabean Revolt. Another focus is the cooperation between Romans and at first Alexander, later the Seleukids. Malalas asserts that Alexander freed the Romans from Persian dominion while they in turn had given the king an army. Since then, a treaty of amity had pertained between the two sides. The chronicler also claims that in his will Antiochos XIII bequeathed his kingdom and all his belongings to the Romans. All this information is certainly wrong, and it is unlikely that Malalas did not know that. This raises the question of how the disinformation entered the chronicle. I shall argue that the errors result from neither a lack of sources nor skill. On the contrary, by analyzing the passages in question, a picture of an intended alteration of history comes to light, one that appears to be rooted in the idea of a translatio imperii.

Christian Michel first gained a B.A. in history and political sciences at the Heinrich-Heine-University Düsseldorf (2012–2015). Consequently B.A. in International Marketing and Management at the Hochschule Mittweida (Saxony) from 2015–2018. From 2016–2018 simultaneous M.A. in history at the Heinrich-Heine-University Düsseldorf. From 2019–2023 postgraduate researcher at the University Duisburg-Essen as part of the research training group 1919 “Precaution, Prevision, Prediction: Managing Contingency” funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, resulting in the doctoral dissertation on “the (political) actions of court eunuchs in the Eastern Roman Empire (395-641 AD)”. Since 10/2023 lecturer in Ancient History at the Heinrich-Heine-University Düsseldorf.

Dr. Pim Möhring, De Nederlandsche Bank, Amsterdam

Engraving History: Seleukid coins in 17th century Dutch literature

In the 17th century, Seleukid coinage was a prominent theme in numismatic studies. Images of Seleukid coins featured in numismatic publications, and writers extensively used them to illustrate historical monographs. An important example of this trend is the monumental work Joodse Oudheden, ofte Voor-bereidselen op de Bybelsche Wysheid (‘Jewish Antiquities, or Preparations for Biblical Wisdom’), by Dutch writer Willem Goeree (1634–1711). Goeree attempts to offer a realistic presentation of biblical history through a multidisciplinary approach, incorporating studies of ancient languages, practices, and architecture. His study of Seleukid coinage was especially comprehensive and eye-catching. Although not a numismatic publication, over half of the illustrated pages feature Seleukid coins, ranging from Seleukos I to Antiochos XIII, engraved in great detail by the celebrated Dutch artist Jan Luyken (1649–1712). Goeree relies on Seleukid coinage for two purposes: establishing chronologies and identifying Seleukid kings. Additionally, Goeree's work includes numismatic corrections to earlier attributions made by renowned numismatists such as Hubertus Goltzius (1526–1583) and Ezekiel Spanheim (1629–1710). In this paper, I will explore Goeree’s motivation to incorporate and study Seleukid coins in a work of biblical scholarship, examine the significance of Seleukid coinage for the (re)construction of history in the early modern period, and investigate the role of these coins in the reception of the Seleukids in the 17th century Dutch Republic.

Pim Möhring is curator at the Dutch National Numismatic Collection of De Nederlandsche Bank in Amsterdam. He studied History at Utrecht University, earning a research master's degree in Ancient, Medieval, and Renaissance Studies. His research focuses on identity in the Hellenistic and Roman Near East, with a special interest in how cities, kings, states, and empires represent themselves on coinage through motifs, imagery, and language. He has published his Seleukid research in Dutch academic journals, focusing on Seleukid hostages in Rome (Roma Aeterna, 2021), Polybios’ perception of Seleukid kings and gold (Tijdschrift voor Mediterrane Archeologie, 2022), naval iconography on Seleukid coinage (Pharos: Journal of the Netherlands Institute at Athens, 2024), and Mysian light-infantry in Seleukid armies (The Seleukids at War: Recruitment, Composition, and Organization, 2024, with Rolf Strootman). He is a committee member of the Sylloge Nummorum Graecorum Netherlands (SNG) project. Currently, he is researching the role of money in constructing identity in colonial contexts.

Raúl Navas-Moreno MA, PhD student at the Autonomous University of Barcelona

The Memory of the Seleukids in the Literary and Cultural Traditions of the Late Antique and Medieval Near East

This paper examines the portrayal of the Seleukid dynasty across late antique and medieval Near Eastern traditions, focusing on their role within broader interpretations of imperial succession in pre-Islamic Iran and the representation of Graeco-Macedonian rule.

A comprehensive analysis of textual sources reveals a range of perspectives. Middle Persian texts, such as the Bundahišn and the Dēnkard, provide limited yet significant references, primarily concerning Alexander the Great. These are followed by works by Persian authors from the Islamic period, including those by al-Biruni, Hamza al-Iṣfahānī, al-Ṭabarī, and al-Dīnawarī, who reinterpret earlier tradition through the lens of Islamic historiography. Additionally, Arabic texts by al-Yaʿqūbī and al-Mas’ūdī, Armenian sources, including the works of Movsēs Xorenac‘i and Step‘anos Tarōnec‘i, and Syriac writings, such as those of Mīḵoʾēl Sūryoyo, reveal a rich tapestry of regional perspectives.

Within the framework of Near Eastern memory on pre-Islamic Iran, the Achaemenids are consistently idealised as the progenitors of a mythical past. Alexander is portrayed ambivalently as a destructive invader undermining Zoroastrianism and, later, as a romanticised Persian hero in late narratives such as the Šāhnāme. The Arsakids, by contrast, often function as transitional figures, bridging the Achaemenid legacy with the Sasanian restoration of Persian hegemony. This study argues that the Seleukids occupy a predominantly negative position in these cultural memories. Frequently portrayed as a transient and disruptive episode, their rule is framed as an unwelcome interlude in the continuum of pre-Islamic Iranian history. These traditions integrate the Seleukid dynasty into a teleological narrative of imperial succession, emphasizing the ultimate restoration of Iranian identity and sovereignty.

Raúl Navas-Moreno is a graduate in Ancient Studies [UAB, 2022] and holder of a Master’s degree in Ancient Cultures and Languages [UAB, 2023]. Currently, he is a PhD candidate in Studies in Antiquity and the Middle Ages [UAB, 2023–2027] and predoctoral researcher (FPU) at the Department of Ancient and Medieval Sciences [UAB], working on a doctoral dissertation entitled The Seleucid Empire and the Iranian world: Sources on interaction, continuity and change in the Hellenistic Near East. His first article ‘Frataraka of the Persis’ was published in Karanos: Bulletin of Ancient Macedonian Studies (7, 2024, 71–97), and his second ‘The Figure of Apollo-Nabû and the Graeco-Mesopotamian Ideological Dialogue’ is forthcoming in the Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions. Has participated in several academic conferences, including: [1] 2ª Jornada científica: La recerca actual en cultures i llengües de l’antiguitat (UB); [2] XXII Encuentro de Jóvenes Investigadores en Historia Antigua (UCM); [3] VIII Jornadas sobre el Mundo Antiguo (UAM); [4] XIth International PhD Conference on Classical Philology: Editing, Commenting, Interpreting: Multiform Apporaches to Literary Text (UAB); [5] 23rd Meeting of Young Researchers in Ancient History (UCM); [6] XIII Congreso Nacional Ganímedes (USC).

Dr. Simone Rendina, University of Cassino and Southern Lazio

Libanios’ “Oration in Praise of Antioch” and the Seleukids

Libanios was one of the greatest Greek rhetoricians of the 4th century CE and the author of a large literary corpus. Since he was born and based in Antioch on the Orontes, where he spent most of his life, his orations and letters provide an exceptional observatory on that city and on its conditions in the 4th century CE, as well as on its previous history, including the Seleukid rule. Libanios’ Oration 11, called the Antiochikos (Oration in Praise of Antioch), devoted much space to the Seleukids, especially to the rulers from Seleukos I to Antiochos IV, and to their legacy in Antioch’s cultural and urban contexts. Although eminent scholars such as Glanville Downey have made fundamental contributions to understanding this oration, several aspects of it merit further investigation. My paper will examine the reasons for the positive reception of this dynasty in Libanios’ Oration 11, and will especially analyse how the founder of the city, Seleukos I, had, according to Libanios, a decisive role in spreading the Hellenic civilization in the eastern, ‘barbarian’ environment. This will shed light on the cultural and political role of Antioch, and of the cities founded by the Seleukids in general, in a multicultural region that was disputed between eastern and western powers. By analysing passages from the Antiochikos, we will thus be able to better understand what the historical role of the Seleukids was according to Libanios, and how and to what extent that dynasty was still remembered in Late Antiquity.

Simone Rendina (Rome, 1989) is a research fellow (ricercatore) in Roman history at the University of Cassino and Southern Lazio. He has been an undergraduate and graduate student at the Scuola Normale Superiore (Pisa) and a postdoctoral fellow at the Istituto Italiano per gli Studi Storici (Naples). He is the author of La prefettura di Antemio e l’Oriente romano (Pisa 2020) and Otto Seeck e il tramonto dell’Antichità (Naples 2023), in addition to other studies on Ancient History, especially Late Antiquity, such as ‘Inviting the Barbarians: Some Episodes of Treason’ (Latomus 79, 2020, 158–183) and ‘Pyrrhus’ Cold Wars: Plutarch ‘Pyrrhus’ 12’ (GRBS 62, 2022, 23–43). His main research interests are 1) the political, social, and institutional history of Late Antiquity; 2) Rome and the Mediterranean world in the 3rd century BCE; 3) the history of modern scholarship on the ancient world; 4) Syriac culture in Late Antiquity.

Dr. Ben Scolnic, Southern Connecticut State University

Creative piece:

An Epicurean Philosopher in the Seleukid Court: Two Letters from Philonides of Laodikeia about Kings He Knew Well

Philonides (c. 200–130 BCE) was an Epicurean philosopher who served in the Seleukid court in the times of Seleukos IV, Antiochos IV and Demetrios I. Two recently imagined letters provide new insights into important but largely enigmatic turning points in history. In the upheaval after the assassination of Seleukos IV by the court minister Heliodoros and the arrival of Antiochos IV Epiphanes, he saved his home city from destruction by the latter. Ironically, it was his lack of concern for worldly things that gave him the stature and relationships to be a factor in real life. His close relationship with Demetrios I, however, led to disastrous results. These letters are expressions of his thoughts at the end of his life as he uses his philosophical tools to analyze his role in the events of his time.

Paper Abstract: The Crystal Coffin of Daniel: Neoplatonic, Early Christian and Jewish Responses to Daniel’s Vision of the Succession of Empires

Ancient kingdoms often claimed to be the legitimate and authentic successors in a line that originated in greatness and legend. In the Biblical Book of Daniel, the succession of kings and kingdoms is used not for the construction of the legitimacy of ruling dynasties, but for the destruction of Seleukid legitimacy in prophetic visions of the end-time situated in a fictional Babylonian or Achaemenid past. The earlier identifications of the four kingdoms represented in the different visions of Daniel, and the determination of the time when the fifth, eternal kingdom would emerge, were not fulfilled in history. This became an opportunity, as the centuries progressed, to re-interpret those identifications and re-determine a new end point for history. The Neoplatonist Porphyry rightly recognized that the last historical kingdom must have been the Seleukid kingdom under Antiochos IV, but he was fought by the Christian exegete Jerome, who engaged in a debate that rages to this day between critical scholars and conservative Christian commentators. Another receptor of these texts is the second century CE Rabbi Eliezer ben Hyrcanus, who represents the relative lack of emphasis on any of this in Jewish tradition. I will then turn to a later Coptic Daniel text that utilizes these texts to predict the end of Muslim rule. The Book of Daniel itself provides a typological hermeneutic that encouraged revision during its development, which then enabled its texts to be applied to new historical situations. Since the prophecies were re-interpreted within the Book of Daniel, it seems fitting that this work became an important vehicle for prophecy and eschatological speculation for over the last two thousand years.